This was initially intended as a presentation, but I thought I might publish it for your consideration. Certainly not my best work and fairly sloppy, but there’s some satisfaction to be gained in trying to grapple with literature you've not engaged with for some time. In addition, I will most likely begin writing my travelogue in the next few weeks, so expect some forthcoming posts on Australia.

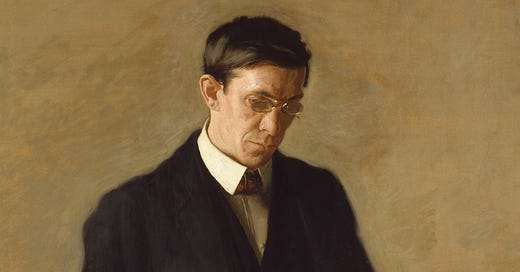

John Williams’s 1965 novel “Stoner” is a work to which the adjectives “unassuming” or “quiet” are typically appended. It received little fanfare upon its initial release and, despite a recent resurgence in interest and critical acclaim, remains relegated to outsider status within the broader American literary canon. Its premise, revolving around the life of the eponymous William Stoner, a farm boy turned English professor at the University of Missouri, does not immediately strike the reader as a particularly compelling subject for a novel; and the prose, described as occasionally wry, highly economical and subdued, leaves little room for embellishment. The author, himself an English professor at the University of Denver, did not expect much of it, writing in correspondence that his greatest hope was that “in time it [Stoner] may even be thought of as a substantially good one.”

William Stoner is a decidedly unremarkable figure and, in many respects, an exaggerated version of the archetypal literary everyman. A shy, timid son of farmers, Stoner comes to devote his life to the study of English upon a chance encounter with Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73, remaining at the University of Missouri as a professor until his death almost 50 years after initially matriculating. For Stoner, the study of literature becomes tantamount to being itself, and the university, as the site of his studies, becomes both a sanctum and a bulwark against the violent, tempestuous forces of an outside world beset by cruel indifference. His life outside the cloistered confines of the classroom is beset by one personal failure after another; his marriage, though initially promising, collapses inwards upon itself, and the emotional bond he fosters with his daughter is severed by his wife’s cold intervention. An affair with a younger colleague - a true intellectual peer - is sabotaged by the spiteful chair of the department in retaliation for Stoner’s earlier failing of his incompetent protege. He only succeeds in publishing a slim volume of literary criticism but, by the time of his retirement, both he and his work have effectively been relegated to that of campus legend.

The story reads as remarkably tragic and Stoner’s life could reasonably be considered a failure; I was left on many occasions emotionally bereft, incapable of continuing the novel for fear of bursting once more into tears. I do not believe, however, that Williams intended to provoke distress amongst his audience; the despair that I, and many others, have felt while reading is merely a product of Stoner’s life coming to intimately reflect the contours of ours. Williams’s prose, though economical, is also remarkably clear, relaying mundane occurrences with grace and sensitivity often absent from consideration within the broader domain of literature and thus giving voice to experiences that border upon being universal. You and I may not lead remarkable existences, but each is beset by both moments of tragedy and ecstasy, love and loss, pain and happiness; they may not prove to be consequential in any respect, but they are still valuable. Like “Stoner”, many of us labor in obscurity, but our dedication, either to our labor, our intellectual or artistic pursuits or our relationships, is enough to imbue our lives with a richness that transcends the fleeting satisfaction of monetary compensation or esteem. We are constantly in a battle to not succumb to the vicissitudinous nature of existence but, when we inevitably retire, it will be the memories of the quotidian that will remain with us, rather than any kind of sublime achievement.

“Stoner” may not be among the greatest novels written in English or even among the greatest American novels, but it is certainly more than just a “substantially good” piece of literature. Rather than acting as a hindrance, it is precisely the “unassuming” character of “Stoner” that allows Williams to successfully coax out the beauty latent within the mundane and, in the process, produce a singularly compelling and emotionally resonant meditation upon how we assess and give meaning to our lives.

"Now in his middle age he began to know that [love] was neither a state of grace nor an illusion; he saw it as a human act of becoming, a condition that was invented and modified moment by moment and day by day, by the will and the intelligence and the heart."

Song(s) Of The Week:

Last week marked the 10th anniversary of the passing of Footwork visionary DJ Rashad, so I’ve thought to include a personal favorite of his in this week’s installment. Enjoy!

DJ Rashad, “Unknown”

Also, this is intended as a facetious nod to the title of the novel (though the song is genuinely entertaining in its own right).

Young Thug, “Stoner”

Now here’s a proper entry to end this week’s installment:

Svitlana Nianio, “Koło Lasu”